shaikezam.com

Step-by-Step Data Integration: Tutorial for Building Robust Star Schema in Data Warehouses

25-08-2024 - Shai Zambrovski

Introduction

In the early days of business data processing, databases were mainly built to manage transactions tied to commercial activities—such as making sales, placing orders, or processing payroll.

These transactions were critical to daily operations, with a focus on ensuring fast and reliable updates to the database as these activities took place.

Over time, the term “transaction” became closely associated with any group of database operations that formed a logical unit of work.

As databases evolved to store a wider variety of data—like user interactions, game activities, or social media comments—the fundamental approach remained transactional.

Applications would typically retrieve and update small amounts of data using specific keys, a method known as** online transaction processing (OLTP)**.

However, as businesses increasingly relied on data for decision-making, a new approach to data access emerged.

This approach focused on analyzing large datasets to extract meaningful insights.

Unlike transactional queries, these analytic queries involved scanning extensive records, performing aggregations, and generating statistics to support business strategy.

This shift led to the development of online analytic processing (OLAP) systems, which were tailored to handle complex queries over large datasets.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, it became evident that using the same databases for both OLTP and OLAP was not efficient.

To better support the demands of data analysis, organizations began separating their analytic workloads from transactional systems.

This gave rise to the data warehouse—a specialized database designed to store vast amounts of historical data and facilitate robust data analytics and business intelligence.

Five key differences between OLTP and OLAP

| Property | OLTP (Online Transaction Processing) | OLAP (Online Analytical Processing) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Manage day-to-day operations | Support data analysis and decision-making |

| Query Type | Short, simple transactions | Complex queries with aggregations |

| Data Volume | Smaller, often gigabytes to terabytes | Large, often terabytes to petabytes |

| Data Type | Current, real-time data | Historical data, often aggregated |

| User Type | End-users/customers via applications | Analysts and management for insights |

The concept of the data warehouse emerged as businesses began to realize that using the same database for both transactional processing (OLTP) and data analytics (OLAP) was not efficient.

Initially, companies used their OLTP databases for both types of operations—managing day-to-day transactions and running analytic queries.

However, this dual use presented challenges, as OLTP systems are optimized for fast, small transactions, while OLAP requires scanning and aggregating large volumes of data.

As the need for in-depth analysis and decision-making grew, it became clear that separating these workloads would improve performance and efficiency.

This led to the creation of dedicated databases for analytics, known as data warehouses.

These specialized systems were designed to handle large-scale data aggregation and analysis, allowing companies to perform complex queries on historical data without impacting the performance of their transactional systems.

Thus, the data warehouse was born out of the need to support robust data analytics separate from the operational demands of OLTP systems.

Data warehouses were developed as separate databases dedicated to analytical tasks.

These warehouses enable analysts to perform extensive queries without interfering with the OLTP systems.

The data warehouse contains a read-only copy of the data from the organization’s various OLTP systems.

This data is either periodically or continuously extracted from the OLTP systems. It is then either transformed into a structure optimized for analysis before being loaded into the data warehouse (ETL: Extract–Transform–Load) or loaded directly into the warehouse where transformation occurs afterward (ELT: Extract–Load–Transform).

Both methods ensure the data is cleaned and prepared for in-depth analysis.

ETL (Extract–Transform–Load) vs ELT (Extract–Load–Transform)

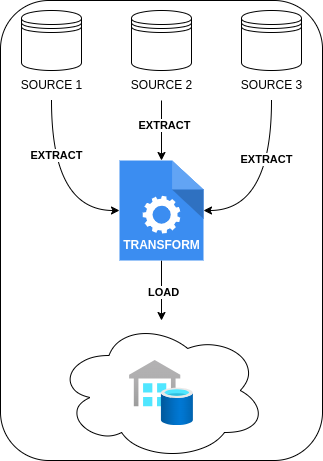

- ETL (Extract, Transform, Load): A data integration process where data is extracted from sources, transformed into the required format, and then loaded into a target system.

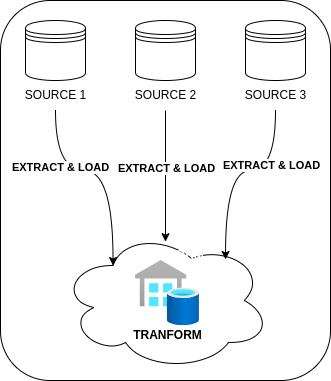

- ELT (Extract, Load, Transform): A data integration process where data is extracted from sources, loaded directly into a target system, and then transformed within the target system.

Differences

| Difference | ETL | ELT |

|---|---|---|

| Order | Transforms before loading | Loads before transforming |

| Processing Location | Uses a staging area | Uses the target system |

| Complexity | Handles complex transformations before loading | Relies on the target system for transformations |

| Performance | May have bottlenecks in the transformation phase | Leverages target system scalability |

| Flexibility | Less flexible for changes | Allows more on-the-fly transformations |

| Cost | May involve additional costs for ETL tools and infrastructure | Typically utilizes existing infrastructure, potentially reducing costs |

| Diagram |  |

|

Data modeling in data Warehousing: Star Schema

A variety of data models are employed in transaction processing based on application requirements.

Conversely, in analytics, data models are less varied. Many data warehouses utilize a standardized approach called a star schema, or dimensional modeling.

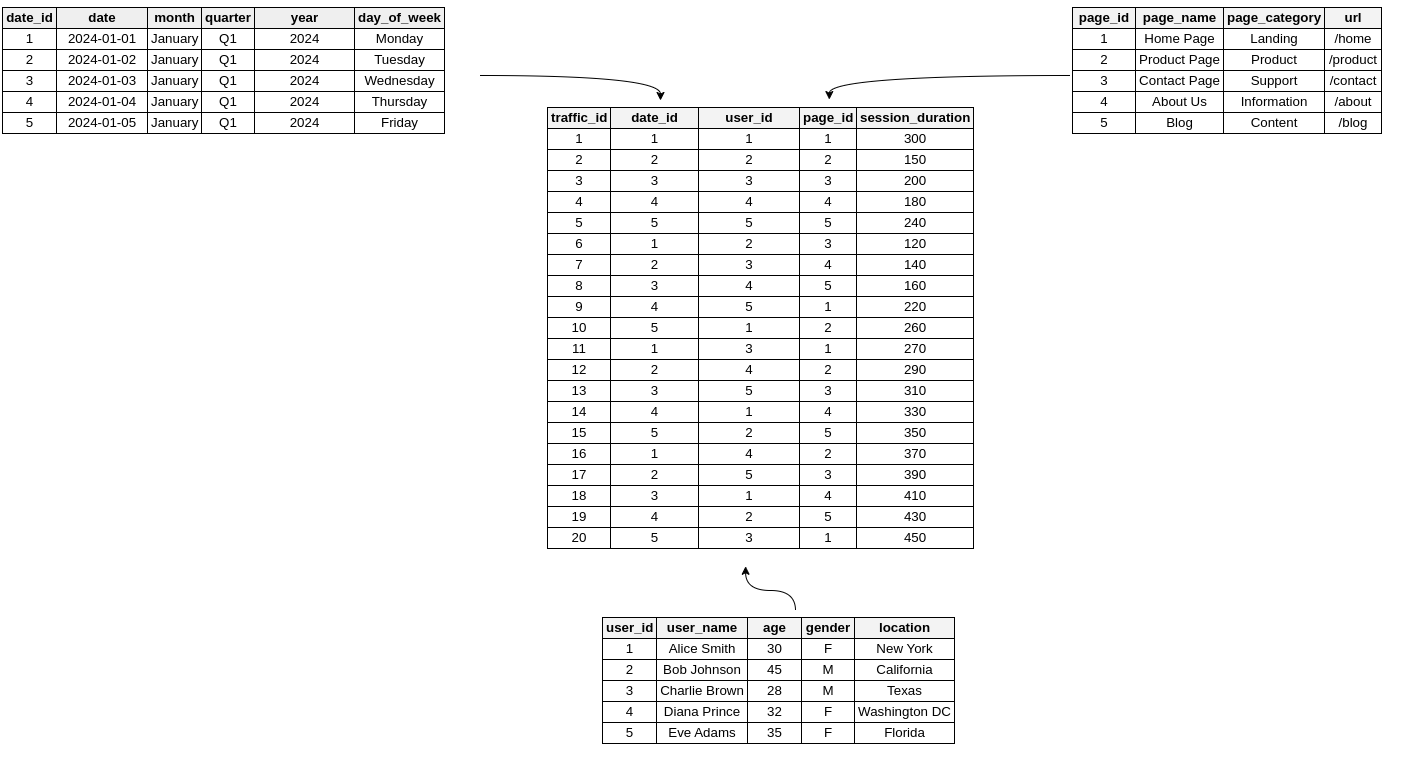

The star schema for web traffic analysis centers around a fact table that captures key events on a website.

In this case, each row in the fact table might represent a significant user action, such as a page view or a click.

This fact table is linked to various dimension tables that provide additional context, such as the date of the event, details about the user, and information about the specific page they interacted with.

These dimensions help in breaking down and analyzing the website’s traffic patterns effectively.

In a web traffic star schema, each entry in the fact table represents a specific event, such as a page view or a click, which allows for flexible and detailed analysis.

However, this can result in a very large fact table, especially for high-traffic websites with extensive data.

The fact table includes both attributes—like session duration or click counts—and foreign key references to dimension tables.

These dimension tables provide essential details about the events, answering questions such as who the user was, what page they interacted with, when the event occurred, and more.

For example, one dimension table might include user profiles, while another might describe the pages viewed.

Time is often managed through a dimension table as well, which enables more sophisticated analysis, such as comparing traffic patterns on holidays versus regular days.

The term “star schema” derives from the layout where the fact table is at the center, with dimension tables branching out like the points of a star.

A related design is the snowflake schema, which further breaks down dimension tables into subdimensions for additional normalization.

This could mean having separate tables for brands and product categories, with each referencing these tables rather than storing the details directly.

While snowflake schemas are more normalized, star schemas are favored for their simplicity and ease of use in data analysis.

In a web traffic data warehouse, tables can be very wide,

with fact tables potentially containing hundreds of columns to capture various metrics.

Dimension tables can also be extensive, including detailed metadata such as user demographics, page characteristics, and referral sources, all contributing to comprehensive web traffic analysis.

Why to use Star Schema in data Warehousing?

-

Quicker Aggregations: The straightforward queries of a star schema lead to better performance for aggregation tasks.

-

Easier Query Management: Star schemas offer simpler join logic compared to highly normalized transactional schemas.

-

Streamlined Business Reporting: Star schemas simplify common reporting tasks, such as period-over-period and as-of reporting, compared to more normalized schemas.

-

Enhanced Query Performance: Star schemas can improve performance for read-only reporting applications versus highly normalized schemas.

How to track changes in Star Schema?

In data management and warehousing, a Slowly Changing Dimension (SCD) refers to a type of dimension where the data remains mostly stable but can occasionally change in ways that are hard to predict.

This is different from rapidly changing dimensions, like transactional data (e.g. product price or quantity), which are frequently updated.

Typical examples of SCDs include things like customer address, product description or even employee job title.

Next, I’ll be explaining the six types of Slowly Changing Dimensions (SCD) used in star schema design for data warehouses.

These methods help manage changes to dimensional data over time, from simple updates to more complex ways of keeping history.

SCD Type 0

| Customer ID | Name | Address |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | John Doe | 123 Elm St |

No changes tracked; the initial data remains unchanged.

Explanation: SCD Type 0 does not track any changes to the data. The dimension is static, and once the data is loaded into the system, it remains as is. This approach is suitable for data that does not change or where historical changes are not important.

SCD Type 1

| Customer ID | Name | Address |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | John Doe | 456 Oak St |

Old data is overwritten with the new data.

Explanation: SCD Type 1 involves overwriting the existing data with new data. This approach does not preserve any history of changes; the most recent data is all that is retained. It is best used when only the current state of the data is relevant, and historical changes are not needed.

SCD Type 2

| Customer ID | Name | Address | Effective Date | Expiry Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | John Doe | 123 Elm St | 2022-01-01 | 2024-01-01 |

| 1 | John Doe | 456 Oak St | 2024-01-02 | NULL |

Tracks historical changes by adding new rows for each change.

Explanation: SCD Type 2 tracks historical changes by creating a new row for each change. It includes additional columns to capture the dates when the data was valid (Effective Date and Expiry Date). This approach is useful for maintaining a full history of changes and is commonly used when it’s important to analyze historical data.

SCD Type 3

| Customer ID | Name | Current Address | Previous Address |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | John Doe | 456 Oak St | 123 Elm St |

Stores current and one previous version of the data.

Explanation: SCD Type 3 keeps track of the current data and one previous version by adding extra columns for the old values. This method allows for some historical tracking but is limited to only the most recent past. It’s suitable for scenarios where only the immediate past changes are relevant.

SCD Type 4

Main Dimension Table:

| Customer ID | Name | Address |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | John Doe | 456 Oak St |

Historical Data Table:

| Customer ID | Address | Change Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 123 Elm St | 2022-01-01 |

| 1 | 456 Oak St | 2024-01-02 |

Stores historical data in a separate table.

Explanation: SCD Type 4 separates current data from historical data by maintaining two tables. The main dimension table holds the current data, while a separate historical table records changes over time. This approach is beneficial for managing large datasets where maintaining history separately can optimize performance.

SCD Type 5

Main Dimension Table:

| Customer ID | Name | Current Address | Previous Address | Address Change Flag |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | John Doe | 456 Oak St | 123 Elm St | Yes |

Historical Data Table:

| Customer ID | Address | Change Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 123 Elm St | 2022-01-01 |

| 1 | 456 Oak St | 2024-01-02 |

Explanation: SCD Type 5 combines elements of SCD Types 1 and 2. It keeps the current data in the main dimension table and maintains a historical record in a separate table. Additionally, it includes a flag or indicator (e.g., Address Change Flag) to signify whether a change has occurred. This approach provides a balance between maintaining a history of changes and managing current data efficiently, especially when changes are infrequent but important to track.

SCD Type 6

Main Dimension Table:

| Customer ID | Name | Current Address | Previous Address |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | John Doe | 456 Oak St | 123 Elm St |

Historical Data Table:

| Customer ID | Address | Change Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 123 Elm St | 2022-01-01 |

| 1 | 456 Oak St | 2024-01-02 |

Combines aspects of Types 1, 2, and 3 by preserving current and historical data through both new rows and new columns.

Explanation: SCD Type 6 integrates elements of Types 1, 2, and 3. It maintains current data in the main dimension table while preserving historical changes in a separate table and through additional columns. This hybrid approach offers flexibility, allowing for detailed historical analysis while keeping the most relevant current data readily accessible.